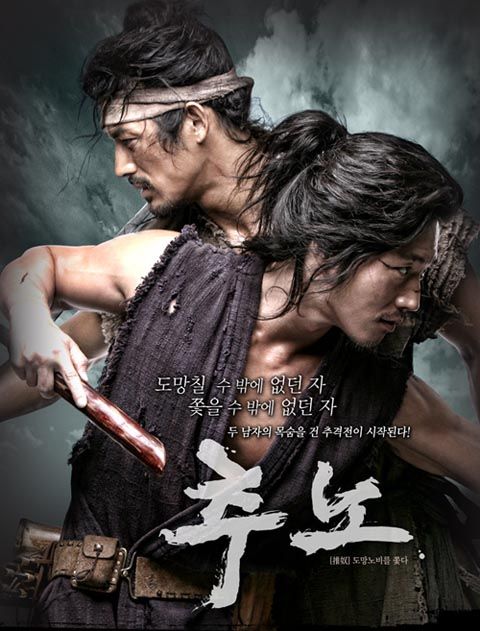

Chuno: Episodes 1-2

by javabeans

Is Chuno exciting? Cinematically stunning? Well-made? Well-acted? Beautifully scored? Entertaining and funny? Yes to all — hell yes.

Is it perfect? Well, no. I’m not tripping over myself to worship at the feet of this drama, although I can see why it might elicit that reaction in others. But there’s no doubt that this drama is going to be HUGE. Possibly Drama of the Year. And most likely, it will deserve it.

SONG OF THE DAY

Chuno OST – “낙인” (Brand) by Lim Jae-bum. This is the song that plays at the end of Episode 1. The title means “brand” as in a branding iron (which is how slaves were marked). [ Download ]

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

BACKGROUND

In the second Manchu invasion of Korea, 1636-37, Crown Prince So-hyun was captured and taken to China, then under Qing Dynasty rule, as a hostage. Eight years later in 1645, he returned to Joseon Korea, but one month later died of poisoning. His wife was accused and given the death penalty by poisoning, and his three young sons were sent in exile to Jeju Island. Two died of illness, leaving only the youngest, Seok-kyun, surviving. In the capital, a power struggle ensued to gain political control. A good half of the common people were made into slaves, often for little reason (such as falling into debt) or as a calculated political move (as in the case of one of our main characters).

Slaves who ran away were rounded up by bounty hunters called chuno-kkun. “Chuno” itself is a portmanteau word combining “chase” with “slave”; hence, slave hunter.

EPISODES 1-2

The year is 1648, the 26th year of King Injo, who is the father of the murdered Crown Prince So-hyun.

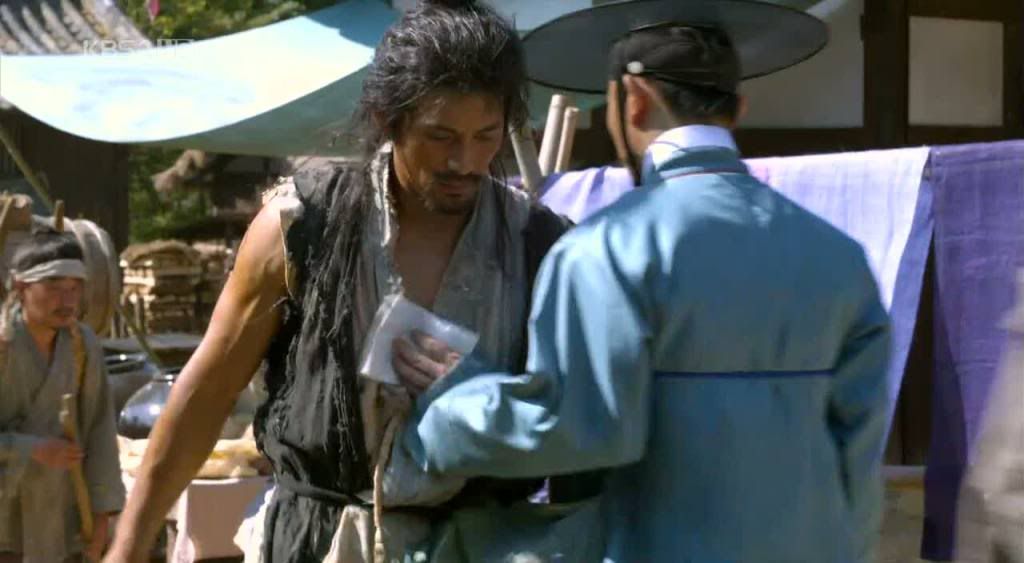

We meet our three bounty hunters as they track down a group of escaped slaves in a tavern-type establishment: they are leader LEE DAE-GIL (Jang Hyuk) and his two subordinates, stoic GENERAL CHOI (Han Jung-soo) and comic-relief playboy WANG SON (Kim Ji-suk).

From there, it’s easy work subduing the runaway party. The three capture the fugitives and tie them up. Leader Dae-gil does offer the slaves one opportunity to save themselves, holding up a sketch of a woman — if they have seen her, he will not only spare them, but help them to safety.

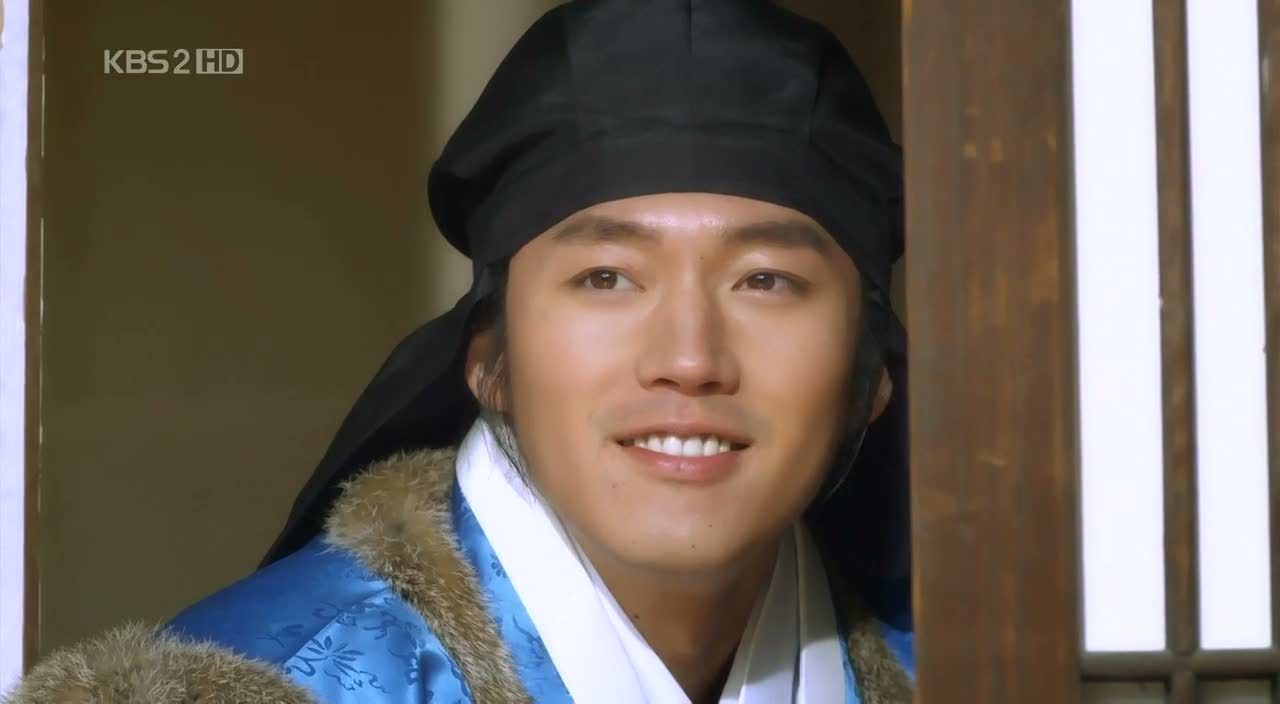

Alas, they haven’t, so the group sets up camp for the night. The youngest bounty hunter Wang Son’s personality is the first to emerge as he complains of being relegated to doing the trio’s “girly” chores — cooking, dishes, laundry. His common refrain throughout these episodes is to get a female slave to do all these feminine tasks for them.

Dae-gil, meanwhile, just stares silently into the fire, impervious to the sobs of the slaves. The mother begs for mercy for her young daughter — if returned, the girl will fall prey to men of the house, who have been eyeing the 13-year-old with sexual interest. Another man, UP-BOK (Gong Hyung-jin) contemplates fighting back with a stone, but falters when Dae-gil asks them if they’ve heard of the slave hunter Lee Dae-gil. They shudder — they’ve all heard of the fearsome, cruel chuno-kkun and beg that he show some mercy, unlike that man. Their hopes plummet when he announces that he IS that man.

In the morning, he hands them over to the police chief, who pays the slave hunters per returned slave. (And tries to cheat him of his price, to no avail.)

Dae-gil’s careless swagger and machismo infuriates Up-bok, but what can he do? Dae-gil is the best slave hunter around. However, Dae-gil’s laughing face immediately turns serious at the mention of UN-NYUN, the woman he has been seeking for a long time. To his chagrin, there is no new information about her.

In another part of the city, SONG TAE-HA (Oh Ji-ho) toils as one of the government slaves serving the state. His work is mostly in the stables, and he keeps his head down and avoids confrontation with others; even when the slave leader bosses him around, he just takes the abuse.

However, he wasn’t always a slave — a flashback shows that he once fought bravely as a government officer himself. In fact, he had served in battle as a general, alongside HWANG CHUL-WOONG (Lee Jong-hyuk), whom he must now serve. Chul-woong is a harsh master who derisively tells his slaves that the horses they tend are worth more than all of them put together. We will later learn that he betrayed Tae-ha in order to usurp his position.

Having completed their job, time for the three slave hunters to relax a little, as well as for us to get the gratuitous completely necessary shower scene of Wang Son and General Choi (whom I’ll just call Choi from here on). Wang Son continues to complain about his girly chores, but when it’s time for him to play, he sure has no problem with the ladies. Each of his encounters with women is played for laughs as they swear undying devotion to him and he’s just eager to get away after a quick tumble in bed.

Choi, on the other hand, is a disciplined man of few words, and therefore attracts the interest of the two ladies who run the place where they stay. He’s not interested but that doesn’t stop the two women from trying, which amuses Wang Son and Dae-gil.

Dae-gil, meanwhile, has a risky relationship with this man, CHUN JI-HO (played with a creepy-but-funny twist by Sung Dong-il), an older slave hunter who mentored Dae-gil and now feels that their history gives him a right to claim him as his own. (He calls him “the puppy I raised.”) Ji-ho wants Dae-gil to work for him again, to which Dae-gil laughs, “How can a tiger work for a dog?”

To illustrate their dynamic, both men laugh heartily at that jibe, and then the smile fades from Ji-ho’s face and he orders his men to attack. But Dae-gil is prepared for this and holds his own admirably, successfully fighting off all his attackers.

In punishment for their sin of running away, Up-bok is marked on the face with a tattoo reading “slave,” while the mother is strung up. The daughter is dragged off to be prepared as an offering for the old man of the house, while the lord’s son enjoys a night of debauchery with his friends.

The young girl begs the old man for mercy for her mother, asking for her to be untied. The old lecher, impatient to get on with the deflowering, reaches to undress her while she cries in fear. He doesn’t get far, however, because an intruder swiftly knocks him unconscious, then rummages through some chests to grab money.

It’s Dae-gil, and he grabs some coins, then offers a hand to the girl. They sneak outside, untie her mother, and steal away to the safety of the woods.

When Dae-gil reveals his face, the mother and daughter gape in shock, recognizing him as the fearsome man who had captured them. He ignores their reactions and instructs them where to go for a safe escape, and where they can find a man who is ready to help them. He also tosses them the pouch of money he’d taken from the nobleman, and saunters off into the night.

The sketches of Un-nyun have been drawn by Artist Bang (Ahn Seok-hwan), who has over the past decade drawn stacks of the same likeness. He points out that her face is likely to have changed a lot — plus, at 25, she is no longer a fresh young thing. Dae-gil might not even recognize her anymore.

Flashbacks reveal the story about the girl, why Dae-gil is so desperate to find her, and why he became a slave hunter:

He had once been the son of a nobleman and she one of his household slaves. To spare her some pain in the harsh winter chill, he had heated stones in his room, which he surreptitiously left out for her to take and use, which she would then return. Their statuses naturally made it impossible for them to be together, but they would take little moments of joy in stolen glances and passing encounters.

In the Manchu war, amidst the chaos and fighting, invaders had raided homes and dragged off their inhabitants. When his home was attacked, Dae-gil had cowered in fear underneath his house, while Un-nyun had been seized by the pillagers. She had sobbed for him, but he had shrunk back, scared, as she was taken.

Mustering his courage, Dae-gil had followed her captor and thrust a blade into his back. The man hadn’t died right away, however, and came after them with his own sword… but they were saved when he was struck down by a Joseon warrior — General Song Tae-ha.

Thus their lives were spared, but when it became known that the young master had fallen for a slave, his aristocrat father wasn’t having it. She was set to be sold off, but the night before, her older brother had sneaked in to save her. He’d freed Un-nyun, then set fire to the house as they made their escape.

However, Dae-gil was left in the house, in shock to see that his parents had been killed. As her brother took her away, Un-nyun had been left with the image of Dae-gil looking out at her from amidst the flames, and her brother had slashed at him with his blade. That became the scar that today graces his left eye, and he has been searching for them for the last ten years.

Dae-gil’s search for the girl is by now common knowledge, so when Wang Son hears about a sighting, he races to inform Dae-gil.

Dae-gil immediately takes off to find Un-nyun in a rush of anticipation, not knowing that she is, at this moment, being married. Now dressed as a fine lady, she goes through the rites reluctantly, shedding tears all the while.

What Dae-gil doesn’t know until he arrives at the supposed location is that Un-nyun isn’t there waiting for him. It’s a trap set by Chun Ji-ho.

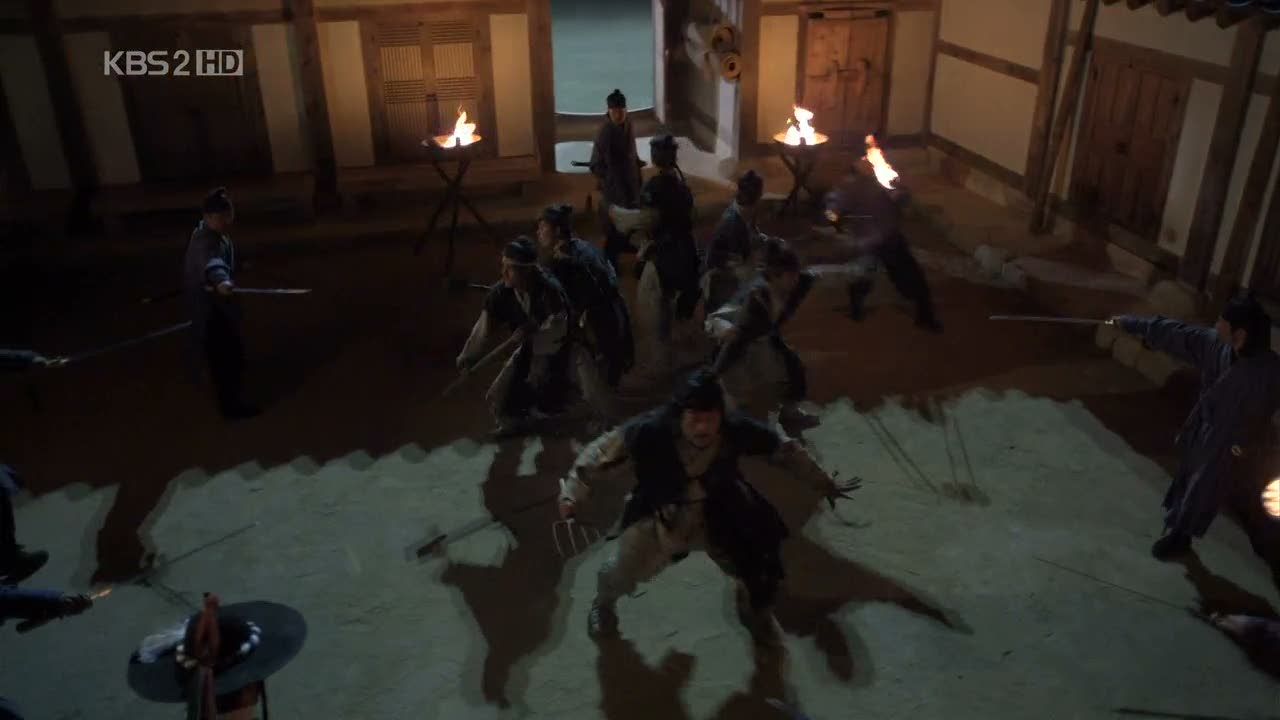

Ji-ho’s man strikes the first blow, and Dae-gil, lost in his deep disappointment, almost doesn’t even register it. Then, in a quiet voice, he warns his former mentor, “You’ve taken the joke too far. Today you’ll die by my hand.”

His numb reaction transitions into fury — at the fact that Un-nyun isn’t here, at Ji-ho for playing with his hopes — and he begins to fight like a man possessed. In another exciting display of fighting prowess, Dae-gil takes on Ji-ho’s men, knocking them all out despite the fact that he’s unarmed and they come at him with clubs and swords. He grabs a sword and puts it to Ji-ho’s neck. Dae-gil is too angry to be merciful and, with a battle cry, raises his sword and starts to slash downward —

— at which point the sword is knocked out of his hand by Choi. His two friends have cottoned on to the trap and have raced here to help, and yell at Dae-gil to remember himself — he doesn’t want to be pegged for murder. Dae-gil doesn’t care, and reaches for the sword again, only to be knocked aside again.

Ji-ho takes advantage of this distraction to scamper away, leaving Dae-gil to take out his anger on his friends for thwarting him. What ensues is another fancy fighting scene as Choi fights back against Dae-gil (and Wang Son pleads ineffectually for them to stop).

Finally, the skirmish ends with Dae-gil holding his sword to Choi’s neck, but the worst of his anger has sapped away. Choi urges, “Let go of Un-nyun now. Even though you met, you never really met, so even though you separated, you never really separated. We call that fate — something that won’t happen just because you want it to.”

A tear escapes from one eye as Dae-gil scoffs, “So now you’re acting like the teacher?”

Un-nyun is now KIM HYE-WON, and now married to a rich businessman, Lord Choi. While she waits in her chambers for her wedding night, she thinks back to the past, when Dae-gil would heat stones for her and say, “I hate you being cold, or being sick, or struggling.” She had asked, “Are you doing this because I’m pitiful? What I want to receive isn’t pity.”

Although he had loved her, he was to be engaged to a woman of his class. He had tried to delay the matter, but had to tell his father that it wasn’t because he was in love — there was nobody like that in his life. Un-nyun had overheard the conversation sadly, but when he came to her in the kitchen, he had silently pulled off her tattered shoes and slipped on a pretty pair. He had told her, “I’m going to live the rest of my life… with you.”

Un-nyun (Hye-won) still has one of the stones with her, and can’t let go of the past. Before her husband comes to her chamber, her brother comes by for some last words, asking her to be happy and move on from the past. Seeing how miserable she looks, he says, “Do you still not understand? You looked at someone you weren’t supposed to look at!”

Hye-won weeps, pointing out that he has killed people, including her young master (she believes Dae-gil died in the fire). Her brother defends himself — he did that so they could become real people — and shows her where a mass of scar tissue covers up the slave brand that had once been there. He tells her, “You must be happy. This is my last wish. Can you promise me that?”

Hye-won replies, “You promise me first. I’ll be happy no matter what happens, so don’t worry about me anymore.”

Hye-won has decided upon her own means for happiness — she dresses in men’s clothing and slips away, leaving her new groom to find the bridal chamber empty. Lord Choi is furious, and her brother apologizes and promises to retrieve her immediately.

To this end, Hye-won’s brother sends his right-hand-man after her, Baek-ho (Danny Ahn), urging him to find her quickly, because if Lord Choi’s men find her, they cannot guarantee that she will remain unharmed. Baek-ho had been once saved by Hye-won and is a man of great loyalty (it is hinted that he also harbors secret feelings for her), so he promises to bring her back safely.

Meanwhile, Lord Choi hires a specialist of his own to bring Hye-won back: this mysterious woman, YOON-JI, who assures him that she’ll bring her back.

Court intrigue: A man pays Artist Bang to reproduce copies of a particular sketch, which are then circulated among the populace. The client impresses upon the artist the importance of this remaining a secret.

This becomes a problem for the royal court, because the drawings depict an atrocity perpetrated among children in Jeju Island. The concerns are presented to King Injo (Kim Gab-soo). The public believes that Jeju was hit by a plague, but the drawings suggest that the inhabitants were murdered through poison, whose effects manifested as an illness, as with the deceased Crown Prince So-hyun.

These drawings are starting to sway public opinion, and people speculate that the children were poisoned in order to kill off the prince’s last remaining heirs, his three sons (two did die, while the last survived). Of course, others find such conspiracy theories absurd — it suggests that the king ordered the murders, and why would he kill his own son and grandsons?

A group of noblemen gather to discuss the matter, and discuss the Jeju Island drawings. They don’t know who did it, but must get to the bottom of this problem. But this group is infiltrated by royal soldiers, who attack the group members, bring them to court for torture and questioning, and accuse them of being the ones who distributed the drawings. This may turn public sentiment and undermine the king, and is therefore an act of treason. Death to all traitors!

The intercutting of these scenes with another high-ranking minister suggests that he has masterminded this scheme.

At the government stables, a group of slaves seize a rare free moment to gather and plan their escape. Tae-ha is excluded from this — he’s the outsider here, even amongst slaves — and they shut up around him. Even when the leader kicks him to the ground aggressively, Tae-ha doesn’t fight back — he has other things on his mind.

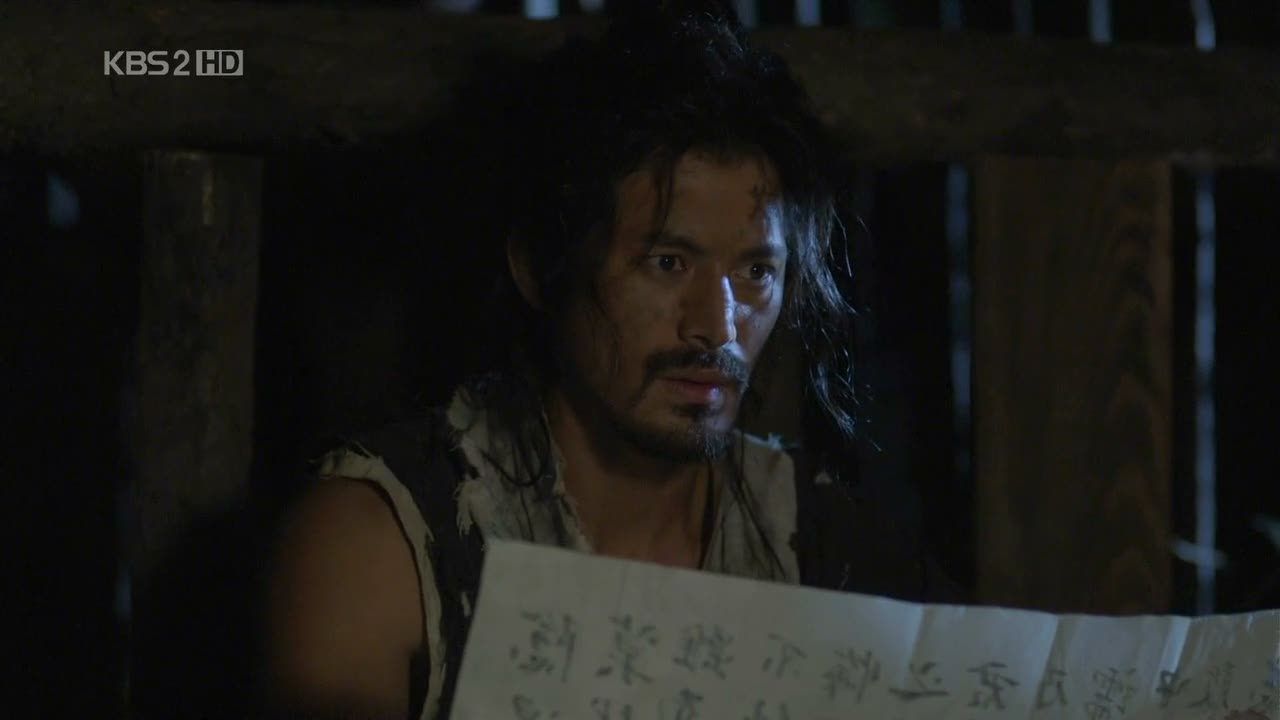

Such as, the letter he was stealthily given. This was written by Prince So-hyun, whom Tae-ha served as a loyal vassal, after the prince had returned to Joseon from Qing imprisonment.

The prince had known he and his family would be targets of assassination, so the letter starts off acknowledging that if Tae-ha is reading this, the prince is already dead.

The letter spins Tae-ha into a flashback of the war, just before the prince was dragged off to Qing. The prince had asked Tae-ha to go with him if they lost, but Tae-ha had vowed to fight to the death and not get captured.

And when the prince had been taken, Tae-ha had watched.

The letter calls him a trustworthy man, and asks Tae-ha to fulfill what he had been unable to. Signing off with the word, “Friend,” the prince had collapsed on the letter, which still bears his bloodstain.

Tae-ha looks at the second paper included in the smuggled letter — the drawing of the Jeju Island massacre, which depicts the lone survivor, the prince’s youngest son.

The other slaves set their escape plan in motion, but they are quickly spotted by guards and sorely outmatched. Quickly, this spins out of their control as the slaves are surrounded. They cling to their weapons desperately and prepare to fight to the death — but proceedings are called to a halt by the arrival of one last figure.

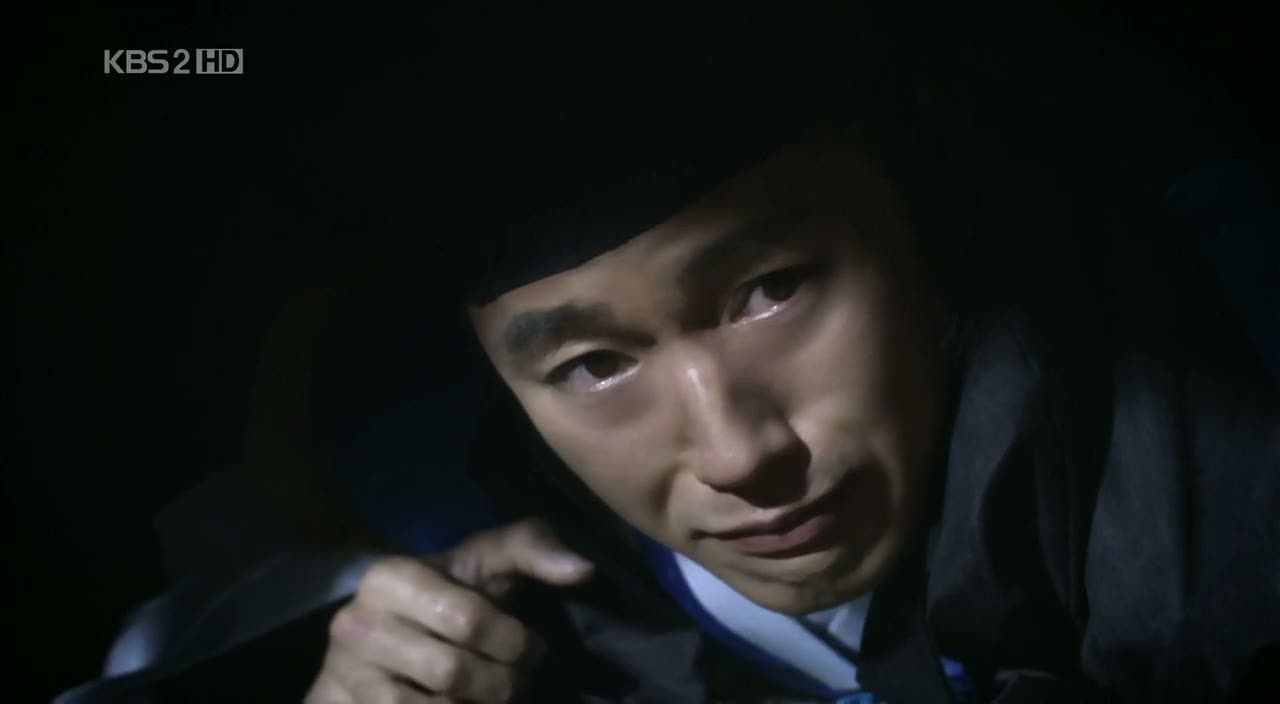

Filled with new resolve, Tae-ha comes out carrying his sword, which had been hidden away in the stable. Because he was always so meek, this transformation shocks the other slaves; Tae-ha spins into action in a sudden whirl of motion. As the guards attack, Tae-ha strikes them down, one by one.

The group goes on the run, and Tae-ha emerges as their de facto leader. Their flight is difficult, however, and by the next day the group is exhausted. They collapse in a field, gasping for breath, protesting Tae-ha’s idea to divert their pursuers in one direction by heading in the opposite direction. They thank him for his help, but as they’re too exhausted to continue, they suggest that it’s time to separate.

Tae-ha warns them not to breathe a word about him even if they get caught — otherwise, he’ll come after them and kill them.

With that, Tae-ha readies to go, but his sudden movement draws the attention of two men in the distance. It’s Dae-gil and Choi, who have been called out to recover the escapees.

The instant the other slaves spot the hunters, they start to scatter, but Tae-ha stands firm. He grasps his sword firmly as Dae-gil spurs his horse on, racing toward him with his own sword outstretched…

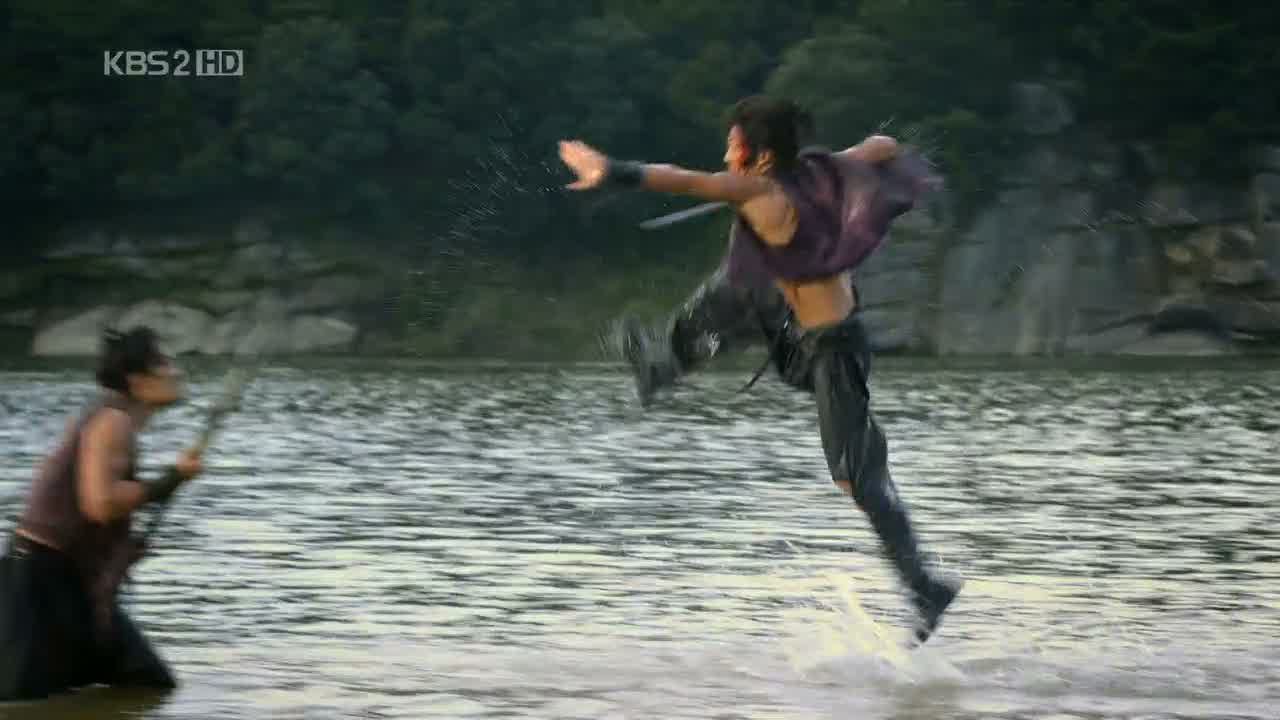

As Dae-gil nears, he swoops low with his sword arm, slashing at Tae-ha. But Tae-ha jumps over the blade, and lands safely on the other side.

Dae-gil falls to the ground, surprised (and a little offended at being thwarted). He glares at Tae-ha, and the two men stare at each other through the tall grass separating them.

Turning toward each other, both men prepare their weapons for another clash…

And charge…

And leap toward each other, blades outstretched….

COMMENTS

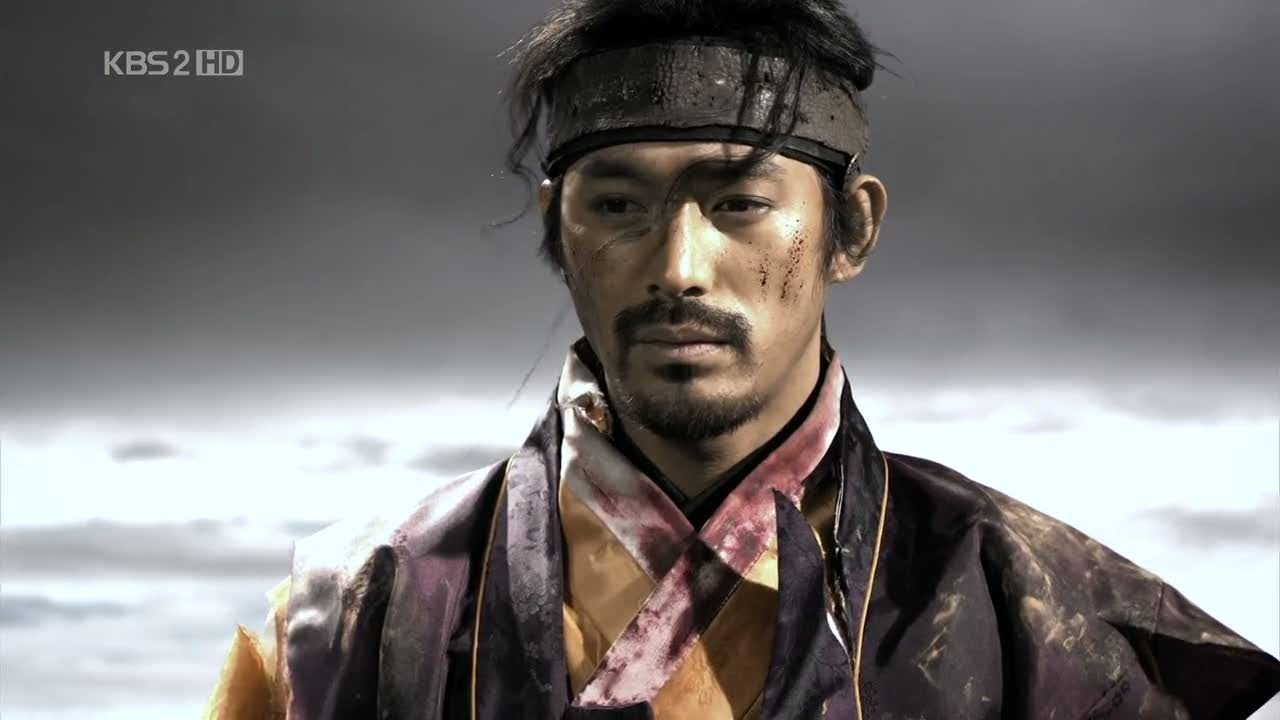

My first thought when watching Chuno was not merely that everything (and everyone) looked beautiful. That’s kind of a gimme. It was that all the actors owe director Kwak Jung-hwan a huuuge debt of gratitude because he makes them look damn near glorious. Every frame depicts the three leads with loving, sumptuous care, captured in their full tortured beauty.

Fighting scenes are detailed in slow-motion to show off everyone’s rippling muscles — only they don’t ripple so much because nobody’s got any fat on their bones — and then super-speed-up to emphasize point of impact. Lingering, hazy flashback shots paint the past as a beautiful, mystical lost time. This drama positively revels in its own gorgeousness.

And if you think it looks pretty in pictures, that ain’t anything compared to how this looks in motion — windswept, bloodstained, glorious motion:

And, to be perfectly honest, I got a little tired of it.

Don’t get me wrong — it’s not like I don’t appreciate a feast for the eyes. I was blown away with the look of Chuno. The cinematography is stunning, the scale grandiose, the music sweeping. And that’s when the drama’s not being humorous and jokey, so it’s not like this is all serious, all the time. It’s only that I got a little overwhelmed with all the fancy tricks, and those are devices that would really be more moving if used sparingly.

It’s like the hero walk. (That awesome walk that you see at the end of movies — slow-motion, wind-blowing-in-the-hair, backlit and reverent.) If you do it once, when the hero has really earned his moment of glory, the audience goes, “Ahhh.” But if you do it every time the hero walks, then you’re like, “Just frickin’ walk already!”

Also, it seems like the director is very much in love with his creation and has indulged himself a little too much. Like that scene of Tae-ha on the bluff, watching his prince being taken prisoner — it’s supposed to be a breathtaking moment, but I laughed. I wanted to feel his pain, but it was like the twentieth Hero Pose we got, and the effect wore off on me. It was like a moment out of Final Fantasy.

Those moments, therefore, feel emotionally manipulative rather than actually emotion-filled. I want to be LED to that moment, not pushed there. I was vastly entertained by Chuno and I’m in awe of their technical achievements, but I wasn’t moved by the stories. I think it’s because everything felt a little slick.

I promise I’ll heap some praise on the drama in a moment, so let me get through minor complaints:

Oh Ji-ho looks amazing and he seems to have improved his acting, but he’s not so great with his dialogue. The flow is off and he hasn’t gotten the knack of natural delivery. He doesn’t have the necessary sageuk gravitas and he tends to get a little mumbly — it sounds so contemporary that sometimes it’s a little startling. It’s the equivalent of an actor in a Shakespearean play speaking with a surfer-dude twang. He looks like a fierce Joseon general, but I keep hearing that plumber dude from Fantasy Couple. I do think he will improve, though — everyone around him is great so it’s got to rub off on him, right?

The writer is Chun Sung-il of the movie Level 7 Civil Servant, and the writing here has the same sort of tendency to gloss over plot points. I really enjoyed Civil Servant and it was heaps of fun, but it has that same slick veneer that works better if you don’t stop to think about the details of what the Russians are really going to do with that biochemical weapon or how to stop them. Nothing is outright illogical here, but some things are done for dramatic effect more than for plot.

Like, for instance, the depiction of Hye-won and Dae-gil’s adolescent love in those halcyon days of yore. I get that the fuzzy focus and soft lighting show that this was a prettier time, but honestly, she was a SLAVE. Her life was not idyllic. (Yeah, I know, it’s his memory, his perspective, blah blah blah. It still bothered me.)

Also, I was annoyed at the way Hye-won is so crushed when she hears Dae-gil is marrying. I understand that it’s a hard thing to hear, but being that she IS his slave, she must have understood from Day 1 that she wasn’t going to get to marry him. So the look of shock on her face, and Dae-gil’s gift of shoes (where is she going to wear those shoes?), just took me out of the moment.

Aside from those nitpicks, I will say that this is an extremely well-made drama, with its production value on par with the likes of IRIS and, uh, just IRIS? Those two dramas have really upped the game for the drama industry, and bring a new meaning to the term “epic.” They make 2007’s Legend look like child’s play. In IRIS‘s case, you could really see the money poured into the location shots and special effects. In Chuno‘s case, the quality is all about the blend of technical proficiency with artistry.

For once, I’m intrigued by the court politics, possibly since this time period is one I’ve seen in a few recent dramas and am interested in seeing from different angles. This isn’t a straight sageuk — it’s fusion — so I don’t expect strict adherence to facts, but that’s okay, since I’m not well-versed enough in this time period to be a stickler. I’m more interested in seeing how they weave their story around the real one.

Everyone is well-cast, from the leads to the extensive supporting cast. Jang Hyuk looks awesome, and he does Dae-gil’s swagger just as well as he does his intensity. Lee Da-hae is wonderful, as expected, and has never looked more gorgeous. Lee Jong-hyuk has not had much screen time, but I think this role is perfect for him — cold, ambitious, brilliant, but backstabbing — and hot damn is that really Danny Ahn as the silent, possibly lovelorn bodyguard? Kim Gab-soo has only been onscreen for a few minutes, but the man has a commanding presence and I’m looking forward to seeing how he plays the treacherous King Injo.

Chuno is certainly exciting, and entertaining. I just wish (really!) that I could feel emotionally invested, but you can’t win ’em all.

And yeah, have I mentioned that it’s frickin’ gorgeous?

RELATED POSTS

- New KBS dramas post strong re-broadcast numbers

- Chuno brings in hit ratings with premiere episode

- Lee Da-hae takes on a male disguise for Chuno

- Press conference day for Chuno

- Chuno boasts a solid supporting cast

- From Chuno’s Jeju Island location shoots

- Chuno’s Lee Da-hae and Oh Ji-ho spend first night together

- First fight between Chuno’s master and slave

- Oh Ji-ho as Chuno’s tortured slave

Tags: Ahn Seok-hwan, Chuno, first episodes, Jang Hyuk, Kim Ji-suk, Lee Da-hae, Oh Ji-ho, Sung Dong-il

![[Beanie Recs] Feel-good fantasy?](https://d263ao8qih4miy.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/BeanieRecs.jpg)

![[Beanie Review] A Virtuous Business](https://d263ao8qih4miy.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/AVirtuousBusiness_reviewb.jpg)

Required fields are marked *

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

51 Beezus

January 14, 2015 at 7:43 PM

Each actor is more handsome than the next! That is; until they show the first one again and the cycle to decide who is finer starts over. My goodness! (And not a flower boy among them!

Required fields are marked *